Every day, we encounter people we don’t know and we make assumptions about them. Consciously and unconsciously, we categorize them based on things like race, age, gender, the way they dress, or speak, or because of the kind of car they drive or phone they use. Our brains are wired to judge others’ behaviors so we can quickly assess who is friend and who is foe. But what do we really know? Many of our assumptions have been influenced by our backgrounds, culture, the media, and superficial interactions. As we mentally process these inputs, we develop stereotypes, resulting in misconceptions and inaccuracies. People are more nuanced and complex than we imagine them to be, and in the world of product design it’s our responsibility to design products and experiences for the needs of real, multifaceted people. At Punchcut we regularly review our approach to UX and research to ensure we’re following ethical and inclusive practices.

Creating Personas from Research not Imagination

Over the past two decades, designers have used archetypes and personas to shed light on perspectives that are different from their own and to help gain alignment for decision-making within an organization. However, the use of personas carries significant risk. While personas can serve as a source of inspiration, their construction and usage is often flawed. Personas are not real individuals, they’re a composite of real people, represented by a single fictional person. Ideally, they are created at the end of a targeted research effort, but the controversy arises when personas are created from imagination, not data.

At Punchcut, we are focused on conscious experience design, mindfully recognizing designers’ impact and responsibility to design ethical systems, and ensuring that research sets the foundation. As UX research experts, we understand the intricacies of human behavior and the importance of preserving the integrity of what we hear and observe from our research participants. We begin our process with foundational research to develop empathy for the people we are designing for and the problems we are trying to solve. Given the breadth of our design research experience, we’ve witnessed how personas can be misused or misrepresented. Here’s how we avoid and overcome the pitfalls.

DO’S:

- Know the target audience for the persona. The data contained within a persona should be relevant to the group who will be using it to make decisions. The needs of a product team are different from the marketing team, and the focus of the persona research should reflect that.

- Do enough research. If the research has too few or too narrow a sampling of users, the personas may not reflect the actual user base. The sample size and diversity will depend on how universal or specialized the product/service is.

- Get stakeholder buy-in. Involving executives, management, and teams in the process of persona creation helps build consensus around what the personas are—and aren’t—and how they will be used.

- Plan for survival. In order to be useful, personas must be kept alive, continuously referenced, circulated among the teams who use them (printed out and easily posted in workspaces and carried into meetings), and refreshed when additional research is conducted. Too many personas are presented once then wither away in a Keynote deck.

Research-Driven Personas in Practice

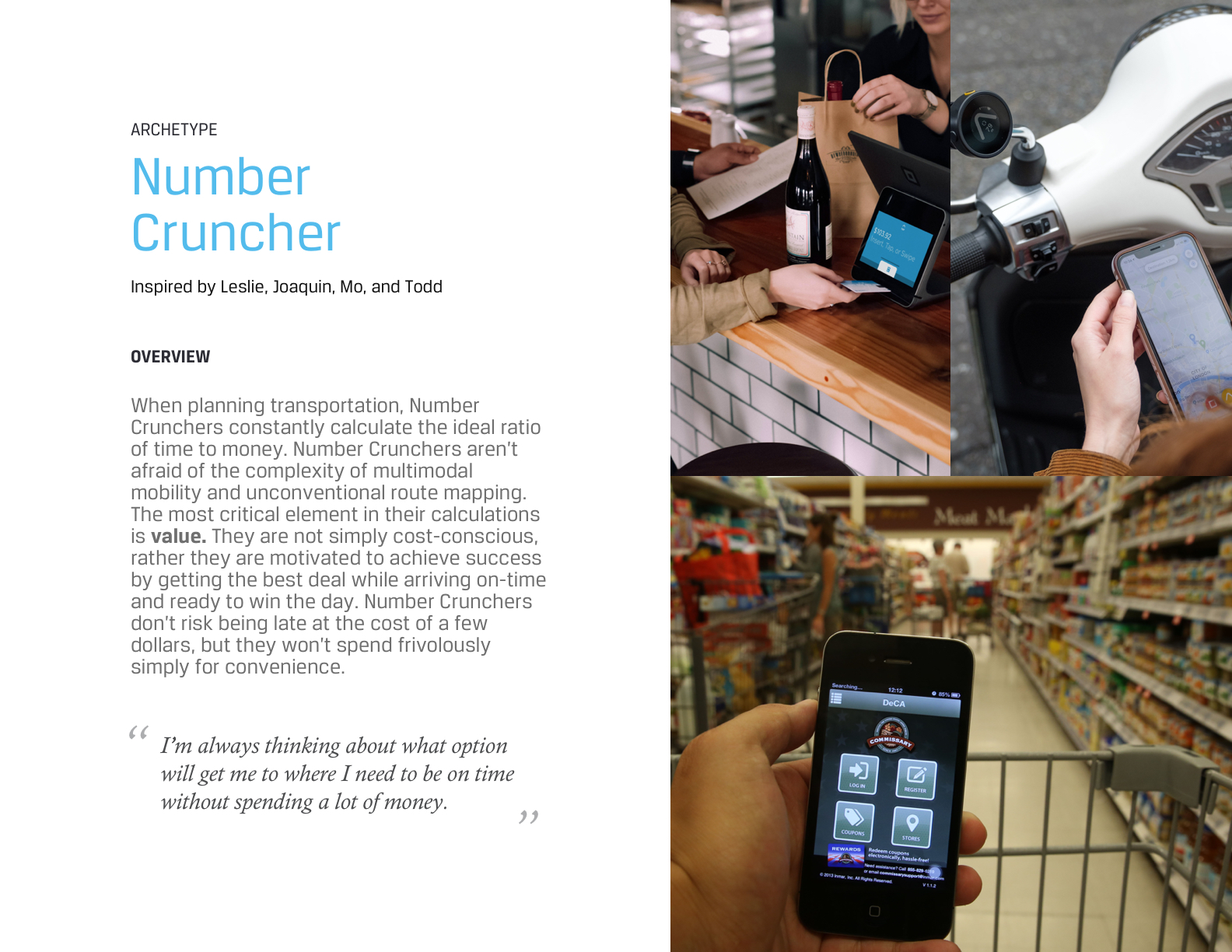

This recipe has proven successful time and again. One of our clients, an autonomous vehicle company, recently partnered with us to conduct a mobility research project. The research effort involved quantitative and qualitative studies in which we created four distinct design archetypes. The goal was to identify and understand their target consumer and figure out how to design for their specific needs.

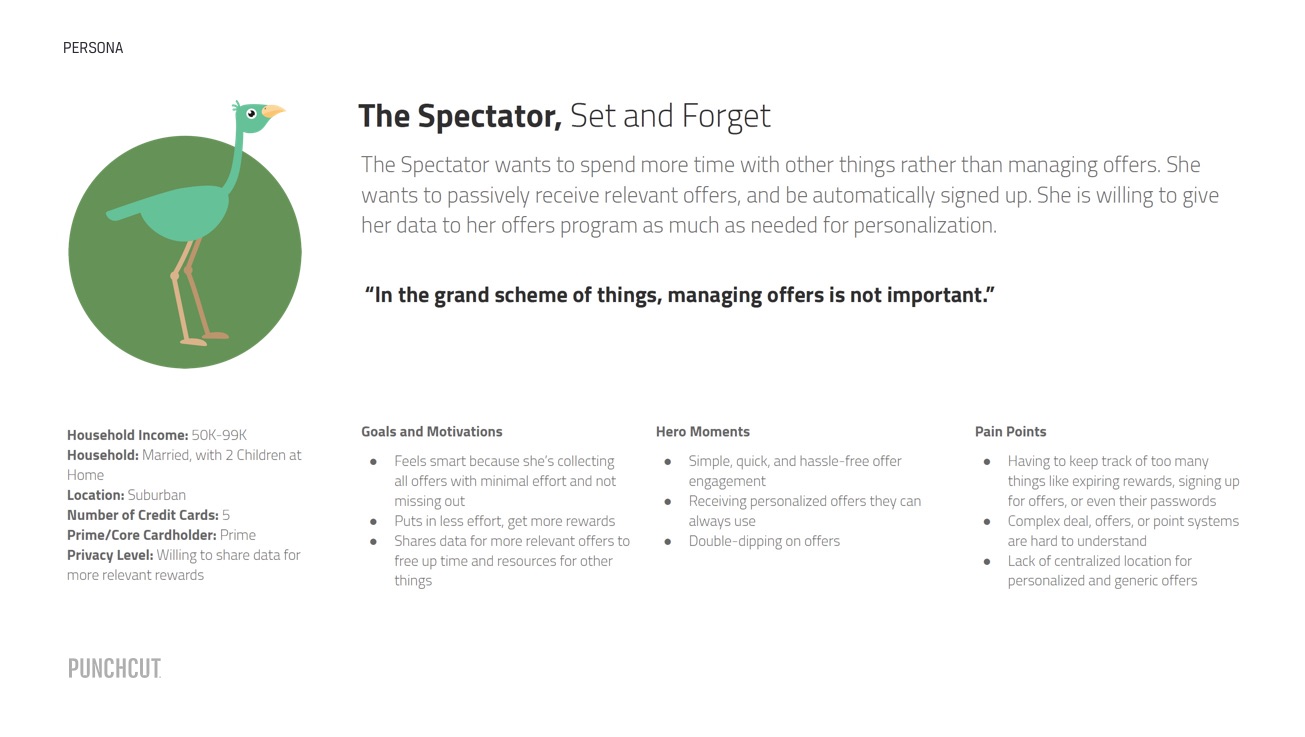

Our investigation started with gathering knowledge about the rideshare population. First, we conducted a survey to identify rideshare users, transportation behaviors, and use cases. We then used that data to inform the recruitment of participants who we interviewed and accompanied on ride-alongs. Our research uncovered experiences and stories and revealed unexpected emotions, priorities, values, and needs. During the synthesis of our data, insights emerged from affinity mapping exercises and we identified patterns that formed into clear archetypes, inspired wholly from our research participants. These archetypes were brought to life as visual and descriptive posters, providing the product design team with a succinct and memorable way to socialize research findings across the organization. In addition, designers could now easily defend their decisions by referencing the archetypes which were drawn directly from real insights and real data.

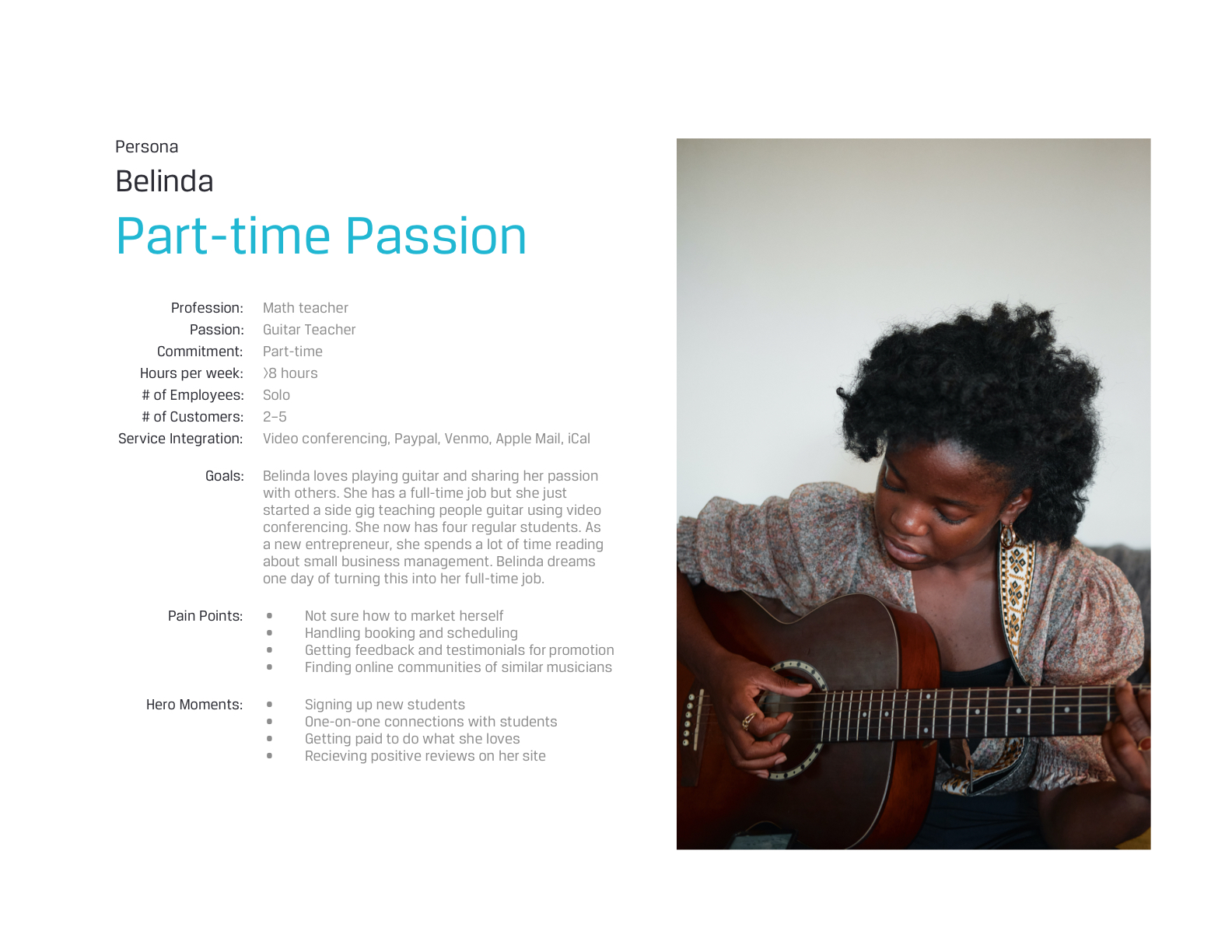

Depending on our clients’ needs, we may either use an archetype in place of a persona or we may take it a step further and flesh out a persona based on discrete attitudes, behaviors, goals, and pain points of the archetype we’ve identified. The primary differences between the two are that an archetype is a more generalized representation (e.g., Penny Pinchers, Goal Crushers) whereas a persona is a personified representative of a larger group, described as a real person (e.g., Maude W. who is a Goal Crusher). When creating a persona from user research, make sure to avoid the following missteps.

DON’TS:

- Loading up on irrelevant demographic data. More often than not, demographic data (frequently helpful in marketing personas) will not help make design decisions, rather it creates bias, not empathy. When crafting a persona, determine if things like age, race, education, family status, and income are relevant to the problems the team will be trying to solve. Depending on the situation, leaving out age, gender, and location and using gender-neutral names can avoid stereotypes and ethnocentrism.

- Creating a generic persona. If the persona’s characteristics and narrative could be applied to almost anyone, more research or analysis is likely needed.

- Creating a “stock” persona. If the persona’s description comes straight out of central casting, and uses glossy stock photography, stakeholders will have a hard time relating or empathizing with the persona. Photos from contextual interviews or photos of everyday people, even illustrations, are more effective and inclusive.

- Adding extraneous details and useless information. It may seem like colorful details like “enjoys knitting and once met Bruce Springsteen” helps to create a multidimensional persona, but unless the organization makes yarn or denim, those details are distracting and unhelpful.

- Charts and graphs that don’t represent measurable data. Don’t be tempted to turn subjective data points into graphs to create an air of legitimacy, or simply to break up blocks of text.

Ultimately, the success of archetypes and personas depends on how well they help to create products and experiences that satisfy the expectations and needs of a specific individual in mind. Imaginary stories of fictional people based on little or no research are detrimental to the design process. Similarly, an unconscious adherence to the UX process can lead to inaccurate personas that may fuel biased beliefs. In our practice, we use research-based personas to not only drive design but also to align the entire team to make clearer, more definitive decisions.

A Punchcut Perspective

Joy Wong Daniels, Principal Design Researcher

Kerry Gould, Design Researcher

© Punchcut LLC, All rights reserved.