Immersive experiences share the same core components as the interfaces we encounter every day. Those experiences bend the UX to the user, enabling us to address the world as we see it: naturally and directly.

Daily interfaces follow a common pattern that allows us to engage, cultivate our identities, accomplish our goals, and disengage. These may be deep, prolonged sessions or momentary fly-bys.

We encounter new interfaces all the time. Fortunately, human beings have gotten quite good at adapting to new experiences. Some interfaces help us adapt to our world. Some interfaces require adaptation, as we bend ourselves to meet the UX.

Immersive experiences share the same core components as the interfaces we encounter every day bend the UX to us, enabling us to address the world as we see it: naturally and directly.

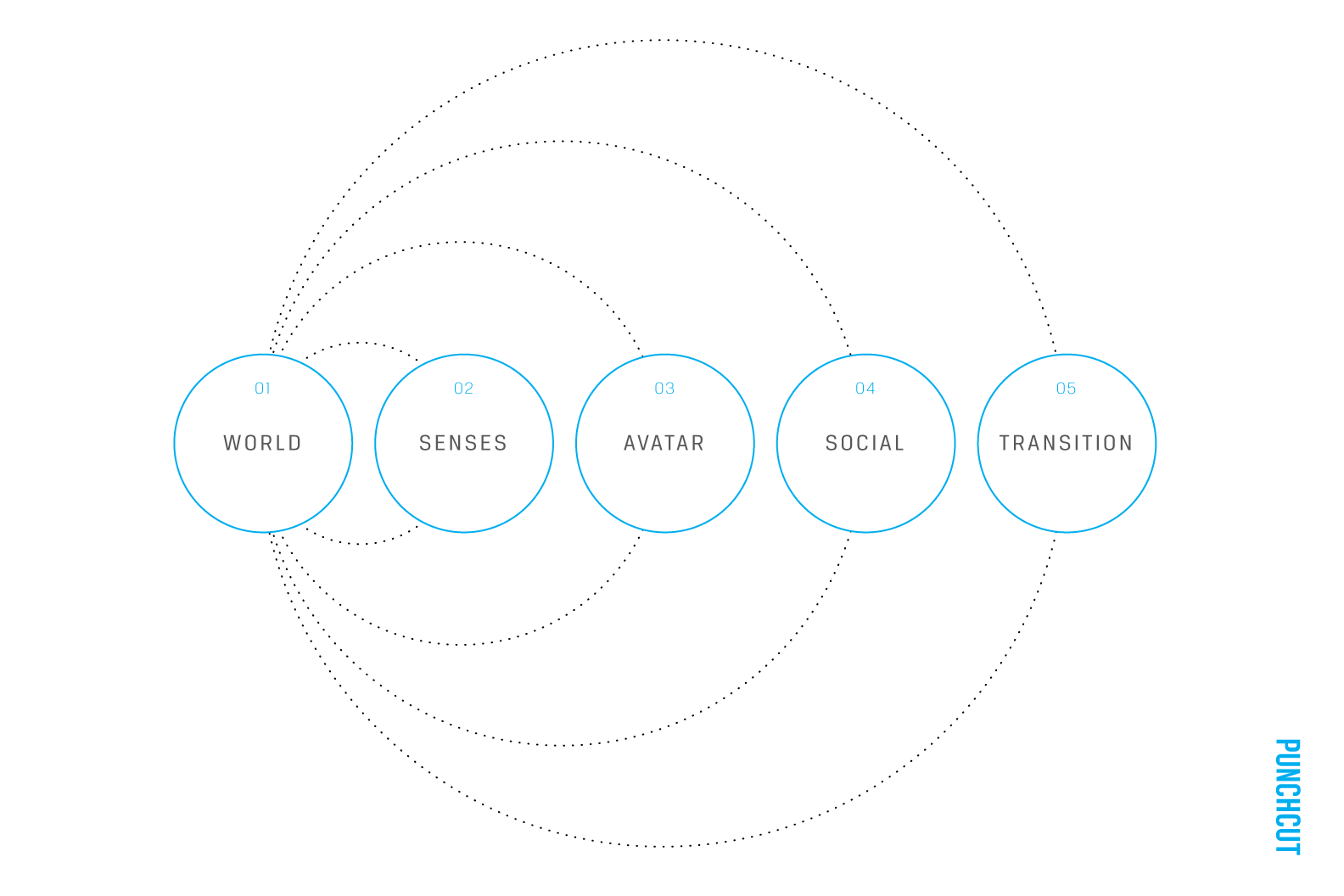

Building upon the Experience Framework for VR, we’ll walk you through five key areas of design insight that will boost engagement with your immersive experience. These have emerged from project work, our direct user research, and lab experimentation.

We’ll touch upon world design, storytelling through our users’ senses, the role of the user avatar, our human need for social connection, and transitioning in and out of the immersive experience.

Bring the World to Life

World-building is the foundation for developing successful VR interactions and interfaces. Letting the user step into a complete and believable environment allows them to suspend disbelief and engage freely with their surroundings. Creating this type of immersive world is about more than just ambient sound and scannable scenery. The physics of the world must be established as well. The more a user buys into the world they are in, and the rules it adheres too, the more immersive and enjoyable the experience has the potential to be. It is the creation of a deep and purposeful environment that is key in building trust with the user, as it allows the environment to grow and change as the user exists within the virtual space.

While many VR experiences are reliant on storytelling and from-scratch world creation, this is not always the case. Medical and engineering applications, for example, are likely to not contain any narrative element. They will, however, still require their own worlds built on rules, architecture, and navigational means to be successful.

A world experienced in virtual reality does not have to be complex to be convincing. Even the simplest of spaces are capable of evoking emotion and having a strong impact on the user. It is worth keeping this in mind when creating content for the VR space and to carefully consider the effect of these experiences on a user’s vulnerability, focus, and expectations.

Fantastic Contraption builds a whimsical world with intuitive controls. There is no gravity or inertia until a user taps a button, however leaving an item floating in mid air and coming back to it later is quickly natural because the rest of the world has been so well established.

Enrich with the Right Senses

A virtual reality designer is a director orchestrating the senses. When a user has the freedom to look in any direction within a large world with seemingly limitless options, being able to focus the user’s attention towards the next objective or narrative moment is key. Providing this focus imbues the user with a sense of purpose (to explore, to act, to witness, etc), which leads to greater immersion and a more seamless experience.

One challenge with design for virtual reality today is the variety of input options that must be considered when creating a virtual experience. Some hardware solutions rely on sight alone, others allow for hand movement or game controllers, and others take advantage of a free range of motion.Virtual experience designers must consider a “responsive” solution to gracefully downgrade for user’s available sensory inputs and outputs.

In designing responsive experiences, the goal should be to keep a users look movement free and not rely on head movement to navigate or select. If all you have at your disposal is sight and sound, consider voice as a “killer app” for virtual experiences. For varying hardware configurations, the pairing of sight, audio and voice as a minimal requirement would still make for a very compelling experience.

When we think about touch, we need to broaden our thinking to account for in-game tactility, feedback from game controllers, and the incidental feel of the floor under our feet. Haptic feedback serves to orient the user, alerting them of changes in the environment. In addition, consider thermoception (temperature) or mechanoreception (vibration). Game experiences like The Void in Lindon, Utah give users a powerful sense of immersion as they sense sources of heat as they pass, or the vibration under foot as they activate lifts from one level to another. Paired with in-experience visuals, the smell of something burning in the air may lead participants forward if such were a relevant clue in the narrative.

The Void bills itself as a “hyper-reality” experience, blending the real world with the digital.

That said, virtual experiences also need to account for senses we don’t often think about. Consider vestibular senses (balance) and proprioceptive senses (the orientation of body position and movement of limbs). When experiences fail to consider these, the user experience greatly suffers.

As a best practice, orient the experience to the user when beginning a VR experience. They should never put on the headset and realize they’re looking at the wrong field of view and have to move their chair/body position to make the experience “work.” Physical comfort is key. For seated experiences, placement of story points and objectives should be within a comfortable angle to a user’s field of view. This also becomes a useful tool in creating meaningful moments pushing a user to look behind them or to feel lost in a space.

With all of these options available to VR designers as methods for directing users through their experience, the art is really in the combination and composition (even exclusion) of these senses to seamlessly move the user through the experience and evoke the desired response.

In Gallery: Call of the Starseed, the user gets haptic, sound and visual clues to solve puzzles throughout the game. For example, the player hears the repetitive sound of breaking glass before looking around to see items being thrown in the air. Seeing a glass fuse in the air, she realizes she needs to catch it before it breaks. Haptics let her know when she’s caught one.

Your Avatar is the UI

The user’s avatar is an important reflection of who they are and their capabilities. Use the avatar to teach your user, always aligning those with available hardware inputs and outputs. Consider tools and menus as part of the user avatar. Of all parts of the avatar, the hands are the most important and can still prove valuable even if disconnected from an avatar body.

There will be a moment in the virtual experience where your user will look down. Whether motivated by curiosity or seeking to better understand their role in this virtual world, looking down and finding no avatar body can be disorienting and unsettling for many.

If possible, allow your user to customize their avatar to improve immersion. Consider gender, body type and skin color that all may be profoundly personal. Consider masking these behind uniforms and/or gloves if customization doesn’t make the MVP.

With Leap Motion, developers are creating UI that tracks directly to your hand movements.

For some users, having a virtual body that is different than one’s own can be liberating. It may allow a user to shed their inhibitions, instilling a sense of bravery and adventure that they otherwise would not have felt. It may allow them to disconnect from real-world limitations or maladies. Virtual experiences have the opportunity to be better than reality, and even feel magical; to experience capabilities that one may not have access to in the real world.

Allowing users to look around without attached UI elements and to instead use their hands to interact with the virtual world is the most important aspect in developing presence. A user needs to inhabit their avatar to feel empowered to take action.

Allow users the freedom to physically look in any direction without unnatural consequences. The now common practice of doing away with traditional HUDs allows the user to focus on the experience and frees designers to create new modes of interaction. Nothing should be attached to a users look control unless carefully placed into a narrative. Some experiences that have a reticle in the center of the screen should only have it available when it’s most needed.

Shift selection, movement, and aim from head movement to a user’s hands.Ideally, hands act independently and are not tethered to a single controller. They should be visible within the virtual space at natural angles to head movement. Map hand and tool actions in virtual space directly to user movements in the physical world. Showing the controllers, tools or available UI elements rendered with (or instead of) hands can orient a user to their abilities. Using gestures to show options is an effective way to reveal menus and tools but still feels part of the experience.

Tilt Brush: Are you painting or dancing?

Invite Social Connections, but Design for Personal Space

As users gain agency in a virtual environment, social connections are a natural step to sharing worlds and experiences. As a spatial medium, the feeling of loneliness may become pronounced. If this feeling is undesirable for your narrative, consider populating the space with other characters, or potentially, other participants.

With a greater sense of presence inside a virtual body there is also an increased awareness of personal space. Proximity to others becomes more affecting and directional sound makes ‘face to face’ conversations quite compelling. This becomes a powerful tool for enhancing game and social experiences, however, a user can also feel vulnerable. Allowing a user to control their distance in relation to others is key for comfort and security.

Personal space also extends to perceived “ownership” of virtual territory. Allow users to build their home environment and dictate terms of social engagement. Establish trust between users with clear spaces for different levels of engagement and vulnerability. For example, a group that often games together may have a common space where they meet and share in addition to public spaces or personal spaces.

Blend Worlds Seamlessly

When one dons a head-mounted display, it’s easy to feel instantly teleported into a virtual experience. As a best practice, provide an introductory or intermediate buffer zone before fully engaging. This initial space gives users an opportunity to get oriented, understand controls and prepare for the experience.

Design for Multitasking

Acknowledging a user’s tech-centered life in a VR environment allows for a more seamless integration into a user’s life.Having access to phone calls, text messages and other forms of communication is important not only for convenience but to maintain immersion in the VR space. Having to pause an experience to answer a call or quickly return a text from within the environment is less immersion-breaking than having to remove the headset and headphones to find your phone or desktop.

Consider Interruptive Use Cases

If a colleague or coworker needs to get your attention while in VR, VR experiences should demonstrate awareness of the “outside” world and provide meaningful feedback to the user. Allow users to virtually “lift the visor” while still in the VR headset by using the forward facing camera to project an image of what is directly in front of them. The headset can adjust lighting and use augmented reality elements to orient the user and ease the transition between virtual and physical worlds. This allows a user to pause an experience without removing or adjusting hardware. This could be triggered by a gesture as an easy shortcut to blend the worlds.

Resurfacing

When someone is done with a VR experience and returns to the physical world, there is often a few seconds to a few minutes of re-acclimation after they remove the headset. This resurfacing should be considered in the development of experiences and use a combination of “lifting the visor”, reintroducing sound and orientating a user as to where they are in the room. The currently cumbersome nature of the hardware should be redesigned to anticipate a user’s intent and smooth the transition back to the physical world.

TL;DR

Immersive experiences naturally lend themselves to longer, deeper sessions. This prolonged period is essential to achieve flow, where the user is no longer concerned with self and is fully engaged with the story and space.The sensory details of our experience can serve to immerse the user further or pull them up and out of it. Both may be desirable as designers transform from interface experts to world creators and storytellers.

—-

A Punchcut Perspective | Contributors: Jared Benson, Ken Olewiler, Joy Wong Daniels, Vicky Knoop, Reggie Wirjadi

A Punchcut Perspective

Contributors: Jared Benson, Ken Olewiler, Joy Wong Daniels, Vicky Knoop, Reggie Wirjadi