With emerging disruptors on all sides, traditional car companies must adapt or face extinction.

The mobility landscape is changing fast. Like the mobile device manufacturers of the early 2000s, car companies of today are being forced to radically rethink their core offering. Like cell phone makers, traditional car companies built their businesses on expertise in hardware engineering and manufacturing, relying on a large network of suppliers, and creating products at scale with long timelines and little input from consumers. In the past, they could focus on incremental improvements to manufacturing efficiency and hardware performance, differentiating their products through branding alone. Today they’re finding their long incumbency challenged by new players with decidedly different strengths.

The New Motown

Big Tech

Today, traditional car brands must compete with Silicon Valley tech giants like Alphabet, Apple, and Amazon—companies with deep software expertise, global brand recognition, and trillions of dollars for investing in innovation. They helped transform the cell phone from a single-function device to a robust platform for a range of services. And now they’re deeply integrated into the everyday lives of consumers in a myriad of ways, offering the full gamut of devices, platforms, and services. Their financial dominance also affords them the luxury of near total freedom to experiment in domains far afield from their core expertise without the need to show any immediate return on investment. With this freedom to fail, they can act as their own disruptors.

New inventions will always be disruptive to the old way.

— Jeff Bezos, Amazon

New inventions will always be disruptive to the old way.

— Jeff Bezos, Amazon

Startups

Car companies must also contend with a multitude of nimble mobility startups like Tesla, NIO, Uber, and Lyft—smaller companies with youthful energy, no burdensome legacy, and little to lose. Without the defensive baggage of the incumbent behemoths, they can pivot relatively quickly to meet changing market demands. They command a workforce of believers—young, eager employees who work long hours with a passion bordering on fanaticism. Currently, this workforce doesn’t fall under the auspices of the UAW, a union that requires higher minimum wage standards and limited working hours. For now, they continue to experience a level of freedom to experiment and iterate, running on private funding without responsibility to public stockholders or trade unions. And with the possibility of acquisition, they may never need to create a profitable business to be successful. Perhaps most challenging is the sheer number of startups out there. Is Uber suffering? There’s always Lyft. Will Tesla last? Well, here comes NIO. There will always be another startup waiting to challenge the king.

Change will require a newcomer to fundamentally design the vehicle differently.

— Padmasree Warrior, NIO

Change will require a newcomer to fundamentally design the vehicle differently.

— Padmasree Warrior, NIO

Driving Factors

Technological Innovation

As ever, this disruption is being driven by technological advances. Smartphones have fundamentally changed consumer expectations for device connectivity and functionality. Like cell phones, cars can no longer survive as the single function devices they once were. Vehicles are becoming platforms, enabled by low-cost sensors and screens, efficient electric batteries, and expanding wireless connectivity. Interfaces are evolving with touch, haptics, voice, and augmented displays. Cars are joining the Internet of Things to communicate with other networked vehicles, infrastructure, people, and devices. And they are becoming intelligent through computer vision, machine learning, and a host of connected data and services. Autonomous vehicles represent the culmination of this evolving intelligence, as the car becomes its own pilot and caretaker.

When you look at the major areas being disrupted in the auto industry, it’s connectivity, it’s electrification, it’s sharing, and it’s autonomous.

— Mary Barra, GM

When you look at the major areas being disrupted in the auto industry, it’s connectivity, it’s electrification, it’s sharing, and it’s autonomous.

— Mary Barra, GM

Sharing & Sustainability

Change is also driven by shifting attitudes around ownership and sustainability. From music to movies to clothing, consumers are increasingly less likely to opt for a small set of privately owned items, and more likely to pay for ongoing access to a massive set of shared goods through subscription services. This inclination is practical—consumers appreciate the variety and immediacy, and can actually earn money through sharing, financing the purchase of a new car by driving for Lyft, or paying for a vacation by renting their apartment on AirBnB. But it’s also a moral and emotional preference—it reflects their desire to participate in premium experiences, but avoid unnecessary waste. As we begin to see the impacts of climate change and air pollution worldwide, consumers feel obligated to make more ethical and sustainable choices. Freedom to escape and connect with people far afield made the automobile king, but in the last decade that has been overtaken by high-speed internet and wireless connectivity. With lagging trends in both car sales and driver’s license adoption in the US, many younger consumers may never even own a car, and those who do are increasingly likely to prefer an electric vehicle.

The goal of Tesla is to accelerate sustainable energy.

— Elon Musk, Tesla

The goal of Tesla is to accelerate sustainable energy.

— Elon Musk, Tesla

Urbanization & Real Estate

Another crucial factor is the continuing trend of global urbanization. Today, over 50% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, and that figure is closer to 80% in most of the developed world. The concentration of wealth and population creates efficiencies, enabling services that would not otherwise be feasible. At the same time, urban real estate prices continue to rise, displacing many and diminishing opportunity for sustainable growth. In many cities, more than 50% of central urban surface area is dedicated to streets and parking, and cars remain parked roughly 95% of the time. Autonomous vehicles could radically reshape urban environments by eliminating the need for extensive parking, reducing the number and size of streets and vehicles, and freeing up large amounts of space.

Emerging forms of mobility, along with a steady increase in people working remotely, could also drive a new wave of suburbanization and exurbanization. Suburbs have always grown up around transport, from the early London suburbs that emerged along railways and underground lines in the second half of the 19th century, to the rise of American suburbs after World War II, with the mass adoption of personal automobiles and the growth of the interstate highway system. New forms of transit could drastically increase the range and speed of transport, transforming huge areas of currently unpopulated and underpopulated real estate, and allowing people to take advantage of cities while living far outside urban confines.

Los Angeles is half parking lots and roads. It’s just crazy that’s what we use our space for.

— Larry Page, Alphabet

Los Angeles is half parking lots and roads. It’s just crazy that’s what we use our space for.

— Larry Page, Alphabet

Health & Safety

Many have pointed to regulation and infrastructure as key barriers to the mass adoption of autonomous vehicles, but governments may soon feel the mounting pressure. Over 80% of people in urban areas are exposed to air pollution that exceeds World Health Organization clean air standards. Much of this pollution can be attributed to greenhouse gases emitted by gasoline engines. This is creating a need for alternative fuel vehicles such as electric and hydrogen fuel cell to help improve local air quality. But perhaps the biggest impetus for swift change is public safety. More than 37,000 people die on American roads each year, and another 2.4 million are injured. That’s about 100 dead and 6,500 injured every day in the US alone. Globally, the numbers are more dire—3,500 dead and 135,000 injured every day. While multiple factors contribute to accidents, including vehicle and roadway faults, human error is the primary contributing factor in over 90% of crashes. In light of statistics like these, the need for change becomes more than just technological convenience—it becomes a moral and ethical obligation to public health and safety. Global regulators have already begun promoting plans to achieve the goal of zero road fatalities, and these proposals rely heavily on the adoption of autonomous vehicles and other emerging forms of mobility.

Our vision is simple: zero fatalities on our roads.

— Anthony Foxx, US Secretary of Transportation

Our vision is simple: zero fatalities on our roads.

— Anthony Foxx, US Secretary of Transportation

Moving Forward

Lessons Learned

When Steve Jobs announced the iPhone in January 2007, Nokia, Motorola, and Samsung were the dominant mobile manufacturers, carriers maintained the principal brand relationship with consumers, and operating systems like Symbian, Linux, and Windows Mobile were widespread but largely unknown to end users. Now, more than ten years after the iPhone’s announcement, Nokia and Motorola are all but gone—chopped up, acquired, and reacquired. Carrier brands reside in the periphery while platforms and services sit foremost in the minds of consumers. Today Android and iOS are the only enduring mobile platforms, and the global smartphone market is shared between Samsung, Apple, and a slew of Chinese manufacturers like Huawei, Oppo, Vivo, and Xiaomi. Of all the major manufacturers from before 2007, only Samsung has really managed to survive and thrive after the smartphone wave. As automotive OEMs face a similar sea change, what can they learn from the mobile disruption of the last decade?

Supply Chain Specialization

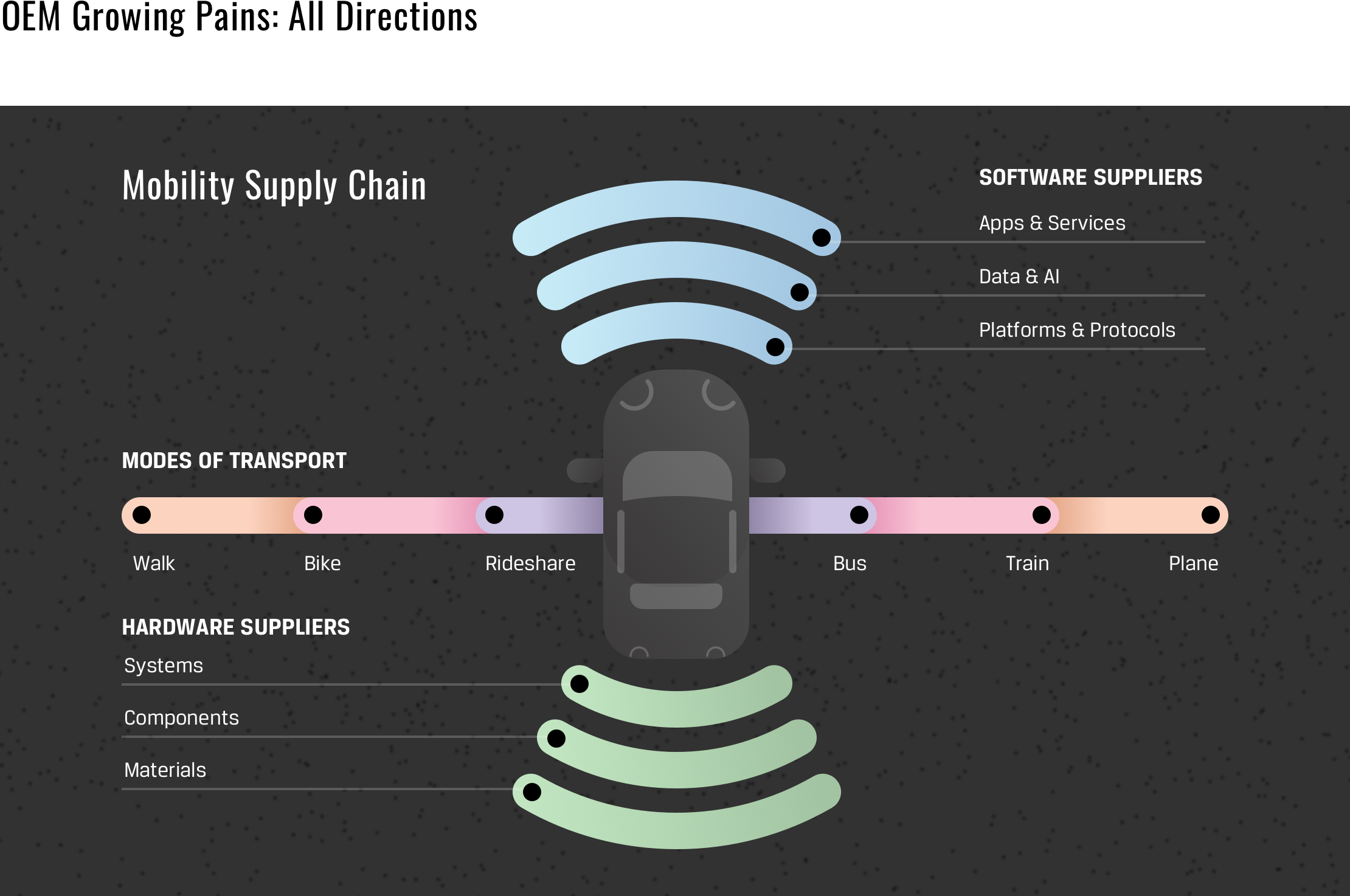

Both Apple and Samsung excel at supply chain management, and it’s a key factor in their continuing success as mobile manufacturers, but automotive OEMs must contend with an even more complex supply chain that’s only getting more expansive. Cars are bigger and more costly than smartphones, and car companies rely heavily on a tiered network of suppliers for raw materials, component parts, and assembled subsystems. As cars become increasingly intelligent, automotive OEMs will become more dependent on software suppliers as well for everything from the underlying platforms and protocols, to the data and intelligence that power key systems, to the applications and services that form the interface layer. With new competitors entering the market from every sector of the supply chain, car companies must think strategically about which elements they want to own and defend.

As Samsung set out to capture the mobile phone market, they bet on specialization in chips and displays, which not only secured these components for their own devices, but also made them an integral part of the supply chain for competitors like Apple. The same thing is now happening in the automotive space. Tesla’s production approach has an unusually high level of vertical integration for an automotive OEM. The company is first and foremost about sustainable power, and they have subsequently specialized in batteries and other electric powertrain components, along with software to optimize energy, safety, and autopilot features. Tech companies like Alphabet are entering with a strong position in software components including platforms, data, AI, and services for both autonomous piloting and user interface experiences. And companies like Uber and Lyft bring an alternative distribution model which turns OEMs into suppliers for their ridesharing services. Car manufacturers have traditionally relied on suppliers for the vast majority of components, and have instead specialized in planning, organization, and assembly. As the automotive supply chain becomes more complex, car companies should consider increasing vertical integration and strategic specialization in areas of the value chain where they can differentiate and defend.

Platform Partnership

Following the announcement of the iPhone, every major manufacturer scrambled to create their own proprietary smartphone platform. Names like Symbian, Maemo, MeeGo, Asha, BlackBerry, Palm, WebOS, Bada, Tizen, Windows Mobile, and Windows Phone have largely come and gone, while iOS and Android have steadily captured and maintained market share. These custom operating systems are costly for manufacturers to develop and maintain, and many companies have failed along with their platforms while others like Samsung, Huawei, and Oppo, that utilized and built upon Android, have fared far better.

Today, it seems like every automotive manufacturer is now scrambling to create their own autonomous solution, their own voice agent, their own HMI layer, and this may not be the best use of resources for traditional car companies. The smartphone has elevated consumer expectations for interface functionality and quality, and if automotive manufacturers can’t meet those expectations, consumers will look elsewhere. People would rather prop up their phone on the dash running Waze or Google Maps than use the native map experiences that currently ship with cars. And third-party developers will be picky about which emerging platforms they choose to invest in. This was a major problem for many mobile platforms, and now iOS and Android, adapted for cars as CarPlay and Android Auto, have an even bigger lead with massive portfolios of existing applications and services. As car companies approach the software side of the modern vehicle, they should be open to smart partnerships for sourcing interface platforms, data, and artificial intelligence, and consider using the application layer to add their own services with differentiating functionality.

Brand Relationship

Before the iPhone, wireless carriers were the primary brands at play in purchasing a mobile device. You’re choice wasn’t between Nokia and Samsung, but between Verizon and AT&T. With the introduction of physical stores and online sales, Apple sidestepped the carriers to sell directly to consumers, and today the networks are the secondary brands. In the automotive industry, car dealerships are the traditional analog of mobile carriers, but unlike carriers, dealerships mainly just trade on the brand strength of OEMs. Tesla has pushed that advantage even further, emulating the Apple model and choosing to forgo dealerships in favor of online ordering paired with physical stores and showrooms located in shopping malls and retail districts. Meanwhile, ridesharing companies like Uber and Lyft are threatening to usurp the customer relationship by supplanting the traditional distribution model based on individual vehicle ownership with one based on sharing and on-demand access. Moving forward, car companies should look to maintain and deepen their brand presence with consumers through prominent marketing and more direct distribution.

While manufacturers are already prolific marketers, the traditional narratives of automotive advertising need to evolve to speak to shifting needs and behaviors. In 2007, commercials from mobile carriers emphasized call quality, network coverage, and rollover minutes, while manufacturers mostly showed hardware glamour shots. Apple chose to focus on the features of the software instead, positioning the iPhone as more than just a physical product and more than just a phone. Now the automotive industry is evolving, and marketing messages must change with it. Car ads tend to focus either on the power of the driver, with glinting grills and revving engines on mountain roads and desert flats, or on the pride of ownership, showing cars in driveways with giant bows on top. The vehicle of the future will not be ‘the ultimate driving machine,’ and it may not be owned at all. Like smartphones, cars are more than just gleaming black boxes, they are the experiences that happen within. Manufacturers must begin to tell the story of what goes on in the car beyond driving, about its features, functionality, and content, and about the larger brand identity and lifestyle promise. These are the stories that inspire consumers to choose iOS or Android, Apple or Samsung, and they will be what determines whether people choose Toyota or Tesla, BMW or Uber.

Service Ecosystem

Finally, automotive manufacturers must begin thinking beyond the car to build a larger product and service ecosystem. Both Apple and Samsung have created robust ecosystems with a range of devices like TVs, computers, wearables, and appliances, and services for things like communication, productivity, storage, media, health, and payment. These offerings provide a more diversified portfolio of earning potential, and create more opportunities for functional synergy across touch points. Automotive OEMs should stop thinking about the car as a siloed product, but as one part of a larger mobility service offering. This means thinking holistically about the mobility journey including planning, departure, travel, and arrival, and all the things that consumers want to achieve or experience while getting from A to B. It means giving deep consideration to the transitions between various modes of transport from walking, biking, and ridesharing to mass transit modes like buses, trains, and planes. And it may also mean investing in emerging forms of travel like high-speed and ultra-high-speed rail, or even supersonic and suborbital air travel. The future of the mobility landscape will look very different than the one we know today, and car companies must adapt to meet the needs of the world to come.

Case Study

A Concept for Change

Emerging transit modes may soon transform our daily travel routines. In anticipation of the coming shift, we created a concept mobility service to illustrate our vision for the future of commuting.

Punchcut

Design for the Future

As specialists in UX for next-generation connected experiences, Punchcut partners with leading automotive and transportation companies to design new travel and mobility experiences for consumers. Our insight-driven methods, in-depth research, and strategic design solutions deliver critical perspectives on emerging technology and human behavior that drive new product ideas and strategies for growth.

Let us know if you have an idea worth chatting about regarding the future of mobility experiences. Odds are we can help out!

Contributors: Nate Cox, Shayne Ingham, Jay Jansen, Shawn Relish, Claire Britt, Kerry Gould, Zach Bass, Jared Benson, Ken Olewiler